By: Andrew K. Bobo and Andrew J. Patton

The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM) digital library contains hundreds of Greek NT manuscripts, each with its own story to tell. In our “From the Library” series, we will feature individual manuscripts from our collection in order to showcase their unique beauty and importance. This is part of CSNTM’s mission to make NT manuscripts accessible for everyone.

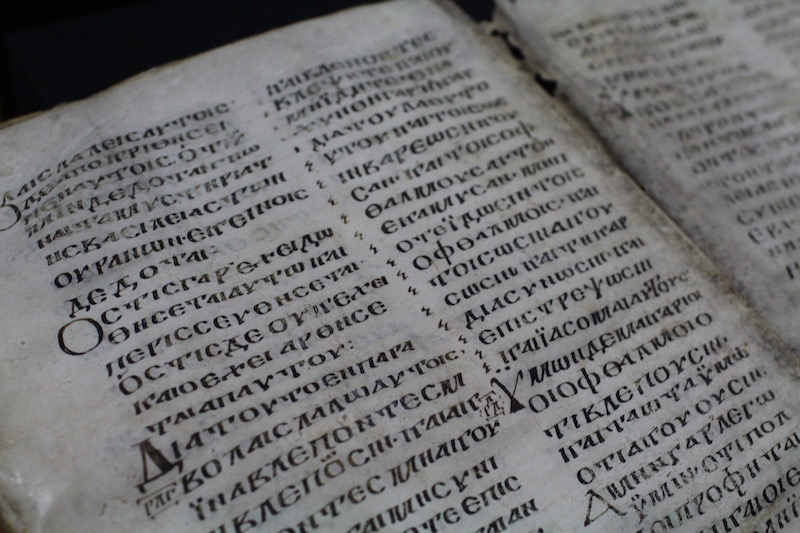

CSNTM’s staff digitized arguably the most significant parchment manuscript we have ever handled at the National Centre of Manuscripts in the Republic of Georgia. Scholars call this famous manuscript Codex Koridethi (Gregory-Aland 038, also known as Θ [theta]). Koridethi, copied in the 9th century, contains all four Gospels written in majuscule script, which means it was written in capital letters. However, we believe the scribe may not have known Greek well because of many unnatural syllable breaks, odd letter formations, and corrections to the text. Koridethi is also an important witness for several major textual variants, such as the omission of “Son of God” in Mark 1.1 and the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 7.53–8.11). This unique manuscript raises interesting questions about our understanding of the relationships between Greek New Testament manuscripts and contains curious oddities in its physical production.

What Text?

Since J. A. Bengal in the 1700s first discussed “families, tribes and nations” of manuscripts, text critics have often divided New Testament manuscripts into categories called text types based on similarities in their texts. The predominant text types that came to the fore were the Alexandrian, Western, Byzantine, and (sometimes) Caesarean types. The past several decades, however, have seen scholars move away from this system because more comprehensive analysis of manuscripts has not only become more possible but also shown that the divisions are not so distinct or definable. (However, Byzantine manuscripts continue to be recognized as a text type because they do have a remarkable degree of uniformity.)

Codex Koridethi is one manuscript that exemplifies the challenge and inherent problems with classifying manuscripts into text types. Studies of the Gospels in Koridethi have shown a partial alignment with different textual traditions—some parts appear to be “Alexandrian,” others “Byzantine,” and still others an idiosyncratic blend. Koridethi exposes the difficulty of fitting some manuscripts into particular categories and further highlights how much work remains to understand the transmission history of our New Testament manuscripts. Accordingly, this manuscript has consistently been identified as a significant witness to the original wording of the Gospels, and scholars producing editions of the Greek New Testament consult its readings whenever they are evaluating a textual problem in a passage it contains.

Imperfect Parchment

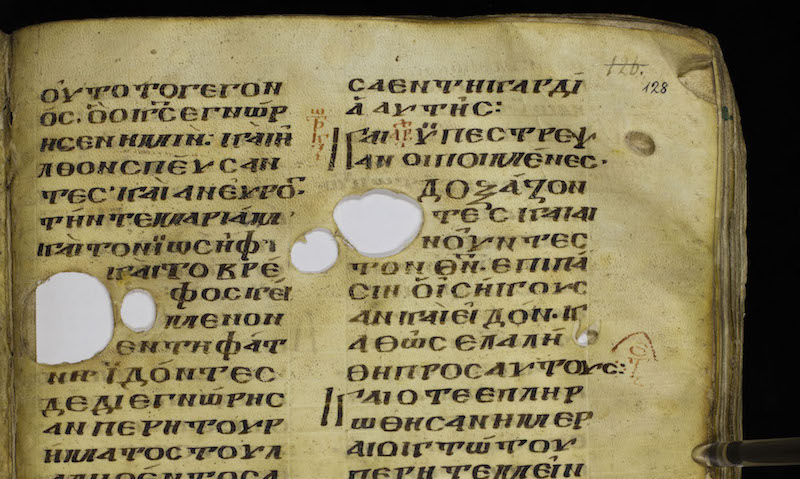

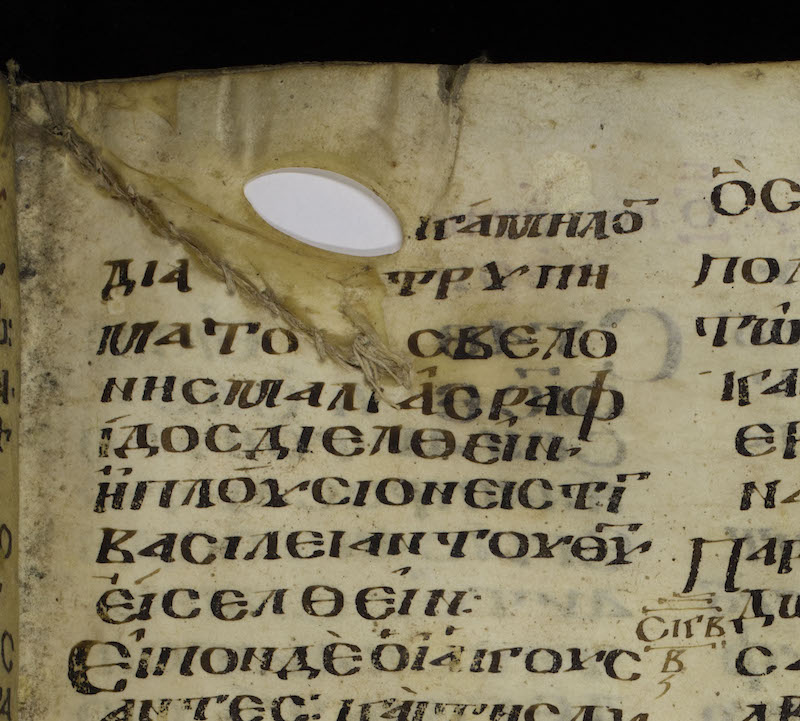

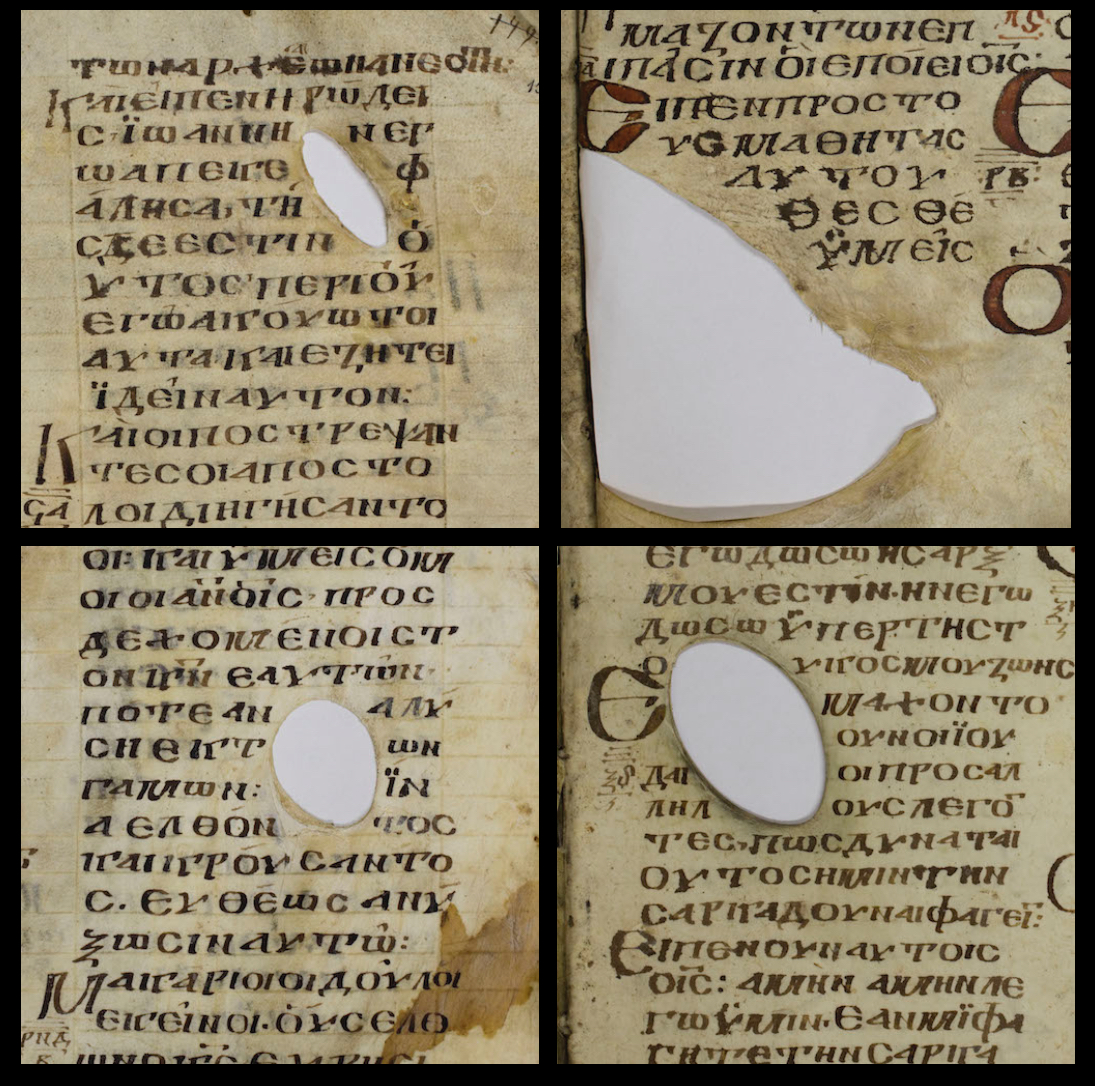

Something you will notice as you scroll through the images of Codex Koridethi are a number of holes in the parchment. It is not unusual that in the daily use of a manuscript there would be damage, tears, burns, or other events that could cause parchment to go missing. But if you look closely, it is clear that the vast majority of the holes in Koridethi’s leaves are original to the parchment’s production. The scribe chose to work the text around them. In a quick search, we found 22 leaves containing various types of production defects. Below are a few examples:

From Leaf 128.

From Leaf 180. Notice that the text is not only written around a pre-existing hole in the leaf, but a tear in the parchment has also been sewn back together, with the text written around it.

From Leaf 151 (top left), Leaf 154 (top right), Leaf 165 (bottom left), and Leaf 212 (bottom right).

In the production of parchment, as the animal skin was scraped and stretched repeatedly, it was easy to scrape a section too thin, which could result in larger and larger holes developing as the skin was stretched to its final size. It is unclear why parchment with such significant defects would have been allowed for use in a Bible, but we can make a decent guess. Parchment, because it is made from animal skins, was highly valuable in the medieval world, and the bill for an order the size of Koridethi would have been steep. So it is possible that whoever produced Koridethi got a bit creative here and was willing to have a few imperfections present in their codex if it meant it could contain all four Gospels. This would certainly have been preferable to undertaking again the laborious and expensive process of producing parchment. Whatever the case may be, the scribe made it work, and this small feature provides us yet another window into the world of ancient book production.

Conclusion

Every manuscript has a story to tell. We are grateful for the privilege to digitize Codex Koridethi and share images of it freely in our digital library. The exceptional staff at the National Centre of Manuscripts are also to be thanked for conserving this codex and collaborating with CSNTM. You can see all the images of this Greek New Testament here in our digital library.

Glad to have found you