By Denis Salgado

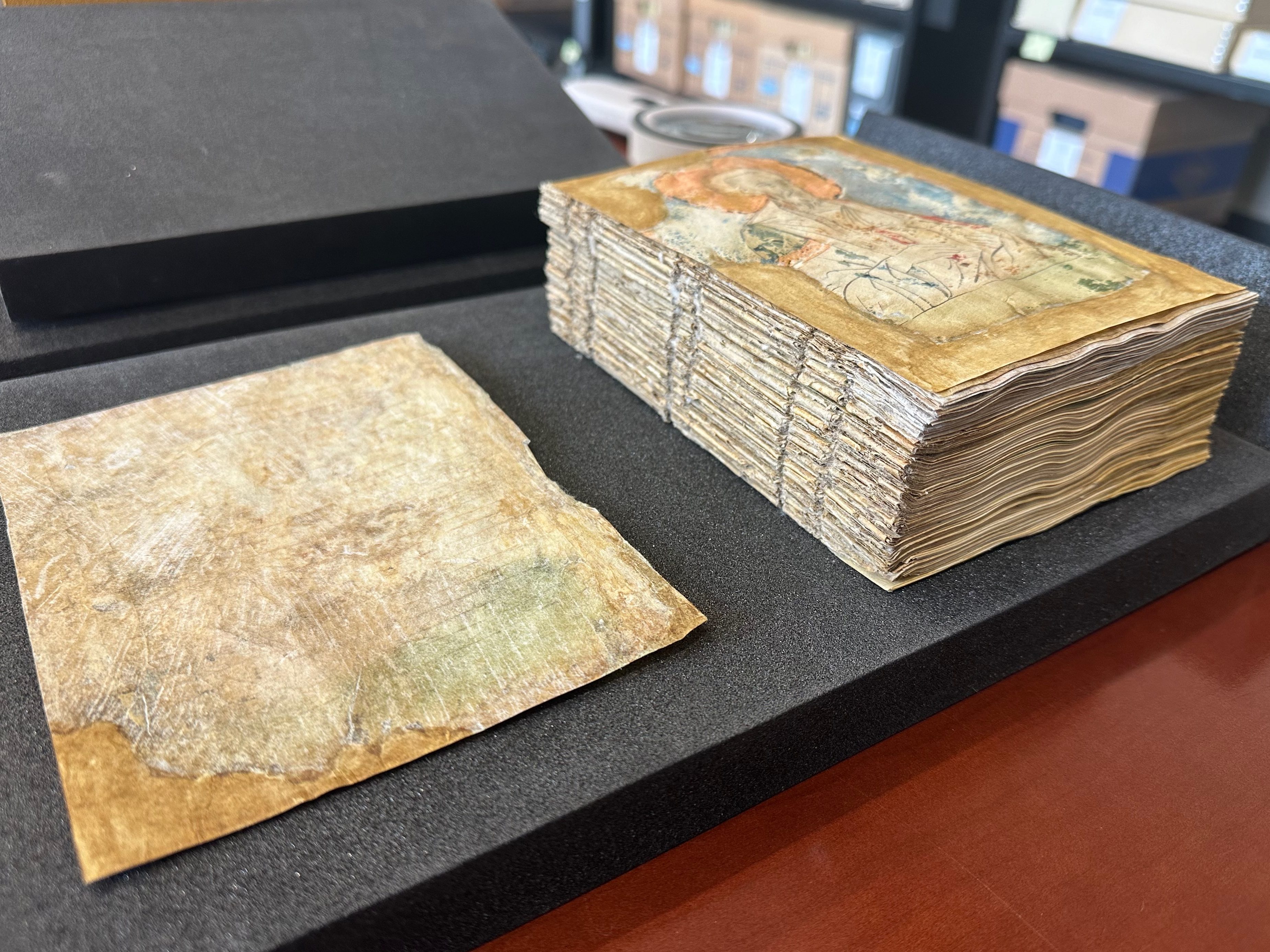

Recently, some CSNTM staff members visited an academic library in the US. Wrapped in cloth, enclosed in a box, and placed in a room somewhere was a New Testament manuscript. According to the official list of New Testament Greek manuscripts (the Kurzgefasste Liste, accessible online here), this document is dated to the thirteenth century. I opened that case, eagerly but carefully, as I have done numerous times in other libraries. I expected to see a parchment codex with modern binding and covers—perhaps brown leather on wood. Contrary to my expectation—and to my dismay—what I saw was simply a tall stack of parchment quires. Several quires are loose, and many leaves are detached from their quires. There it was: a parchment manuscript, produced in the thirteenth century, carrying a portion of the New Testament in Greek written about seven centuries ago. No cover. No binding. The only thing currently holding those stacks of quire together is the case.

Considering its current physical condition, it is no surprise to know that certain quires and leaves are out of order. Perhaps the last person who consulted the manuscript accidentally misplaced them. It is also possible that those in charge of caring for this book have limited knowledge of Greek and the New Testament text—they were unable to identify the content and arrange the material in its proper sequence. Whichever the case, the point is the unfortunate physical state of this document that is precious to those who not only value it as an artifact but also to those who highly esteem the content it still preserves.

As an artifact, this is no boring manuscript. Those interested only in questions related to the text of the New Testament perhaps content themselves with reading and analyzing hundreds of consecutive lines of text. However, this document contains several features that make it relevant for other types of investigations.

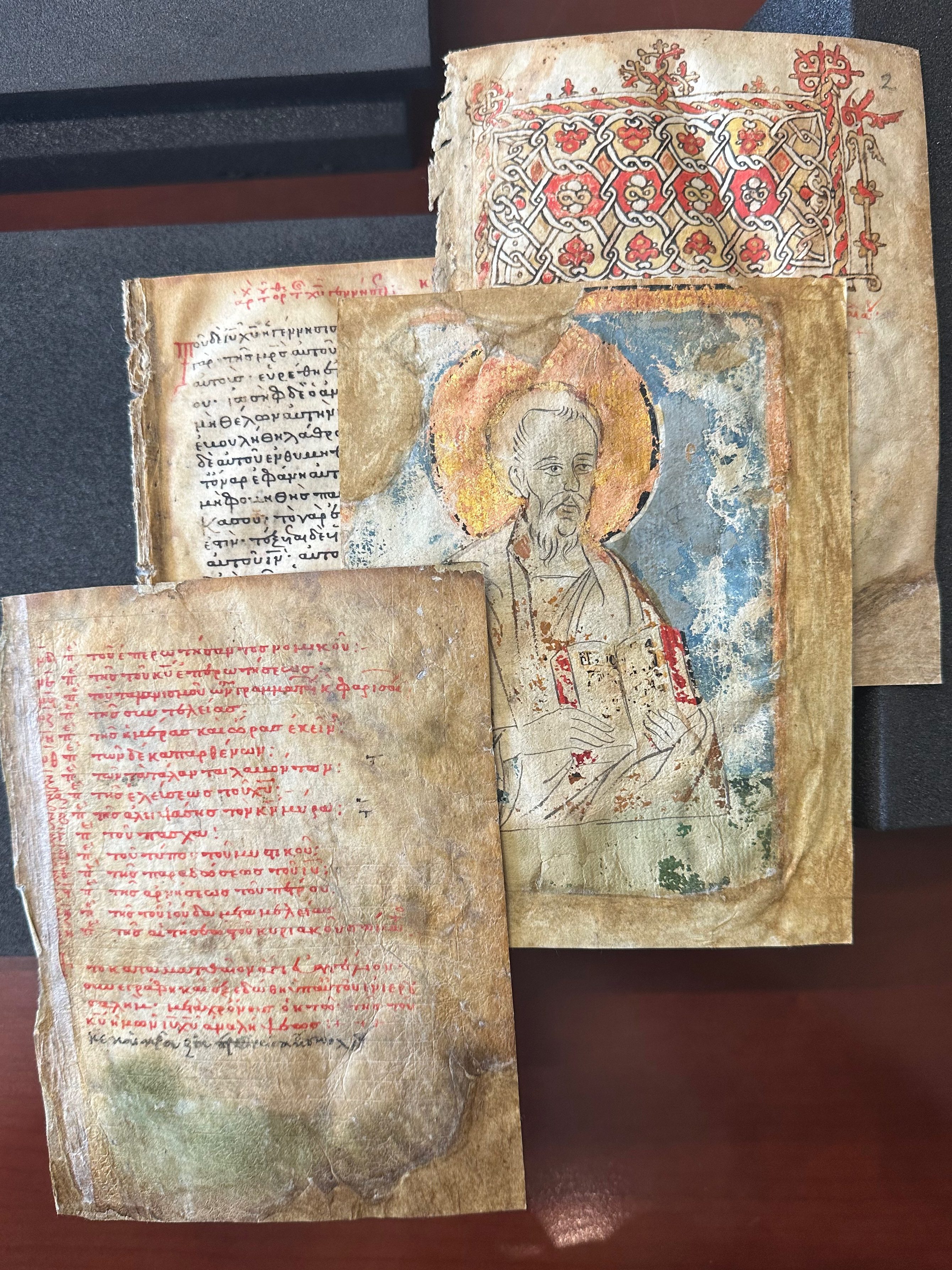

For one, it is relevant for those interested in Byzantine book art and illumination. The Gospels are preceded by full-page portraits of the Evangelists. Besides being significant for art historians, the leaves with the portraits are also relevant for codicology because they were added at a later stage in the history of the document. In addition to the portraits of the Evangelists, ornamented headpieces in multiple colors mark the beginning of each book. Unfortunately, however, the ink has washed off at several points, especially in some of the portraits. The same is true, albeit to a lesser degree, of some of the headpieces. Has this happened because of the rather poor condition in which the manuscript has been stored over the years? Perhaps it is no coincidence that the portrait and headpiece that have suffered most decay are the ones of Matthew—these leaves sit at the top of the stack of quires. If we photograph the manuscript using a color target, conservators will be able to determine a decade from now the rate of deterioration of the ink and adjust storage practices accordingly. This is all part of the history of the manuscript.

Besides art history, the document preserves paratextual features that make it relevant for those interested in the development of Christian traditions beyond the text of the New Testament. For instance, the leaves are marked with lectionary notation, that is, the biblical content is segmented according to the reading schedule of the communities that produced and used the manuscript. These features are crucial for those in the field of liturgical studies interested in the lectionary systems. Additionally, the biblical books are accompanied by kephalaia or headings that help readers locate specific sections in a given book based on content. Once again, the list of headings for Matthew is only partially extant—only the last leaf remains. This leaf is the first on the stack and is detached from the quire to which it originally belonged. Since the library has no information as to when the manuscript was disbound, then we must consider the possibility that the previous leaves may have been lost after the manuscript came into the possession of its current holders. If such was the case, then this manuscript is no longer as useful as it once was for certain types of investigation due to its poor state of preservation.

That manuscripts have suffered all sorts of damage throughout history is no news. Documents were destroyed, looted, or damaged during the Crusades, fires in Medieval monasteries, European wars, and in one of the many conflicts that so incessantly disturb the Middle East. It is rather unfortunate, however, to see manuscripts suffering damage and accelerated decay in contexts where considerable resources and specialized personnel are available.

On a rather practical side, keeping a manuscript in the condition described above makes it more susceptible to theft. Single leaves of valuable documents are often put up for sale in the illegal market. Photographing the manuscript, providing a detailed description of its structure and content, and rebinding the codex are essential steps to prevent the work of white-collar criminals.

Sadly, it is not uncommon to find manuscripts stored in a similar physical condition as the one described above. This codex is just one more reason why we do what we do. At CSNTM, we are committed to the physical and digital preservation of ancient artifacts, especially those that have transmitted the text of the New Testament. It is by collaborating with individuals and other institutions that we can ensure that these precious documents are preserved and made widely accessible in digital format.