By: Johnathan R. Watkins and Leigh Ann Hyde

In the pivotal scene of the 1965 holiday special “Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown,” the lead actor reaches a moment when he can no longer contain his exasperation. He failed to direct the Christmas play, he failed to understand the growing commercialism, he failed to pick out an appropriate Christmas tree, and finally, Charlie Brown yells out in distress:

“Isn’t there anyone who knows what Christmas is all about?”

From the crowd emerges an unlikely hero. Wielding only a security blanket and the text of Luke 2:9–14, Linus Van Pelt sets Charlie Brown straight on what Christmas is all about. It is a beautiful moment highlighted by Linus dropping his blanket as he utters the angelic command “fear not.” The scripture lesson corrects Charlie Brown’s perspective on Christmas. Even more, the whole Peanuts gang seems to suddenly get the spirit of the season.

The hustle and bustle of the holiday season can lead to “Charlie Brown-like” levels of exasperation for anyone. Coupled with COVID-19 and all the new challenges we face, the sentiment is likely exponentially multiplied in 2020. And yet, the text of the nativity account preserved in Greek New Testament manuscripts is exceptionally stable, inspiring something more like Linus’ confidence than Charlie Brown’s discouraged distrust. Given the witness of the New Testament textual tradition—we do know what Christmas is all about.

In the Manuscripts

The Christmas story, including the text Linus quoted, appears in Matthew 1–2 and Luke 1–2 in the New Testament. Before animated movies and printing presses, the story passed down through handwritten copies of the text. The New Testament boasts of an impressive textual tradition. As we might expect, the nativity account appears in a great number of manuscripts that span the centuries. Over time, as the handwriting, materials, and look of manuscripts changed, scribes continued to copy the text of Matthew 1–2 and Luke 1–2. Let’s look at some digital images of the early books that contained the Christmas story.

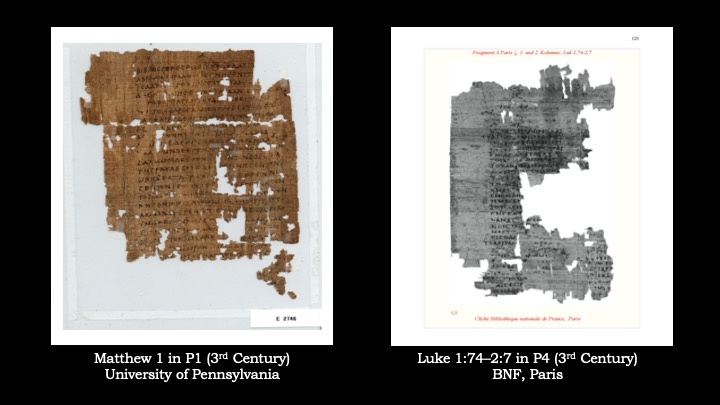

All four chapters appear as early as the third century in papyrus manuscripts. The oldest copies of the New Testament text appear in the papyri, the earliest dated to the second century by papyrologists, an ancient writing material made of the systems of a papyrus plant. Age and use caused great deterioration for many New Testament papyri which now exist as fragments. Yet, the text they preserve has proven valuable to text critics who utilize these early resources to determine the original message copied down. See below two papyri that contain the earliest evidence of the Christmas story we have today.

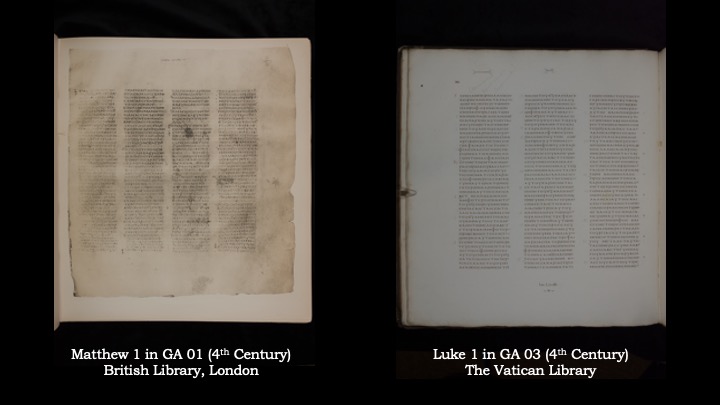

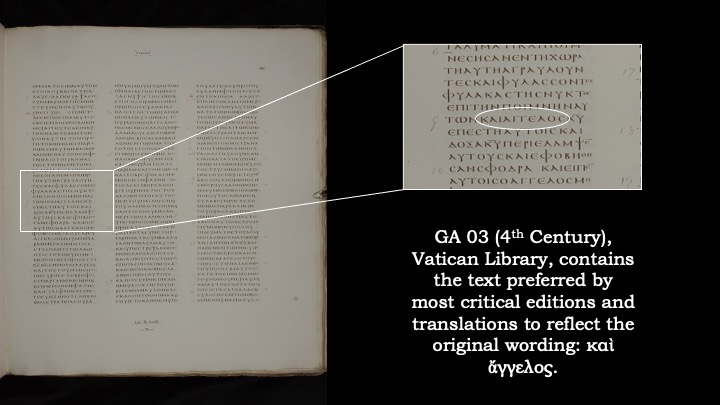

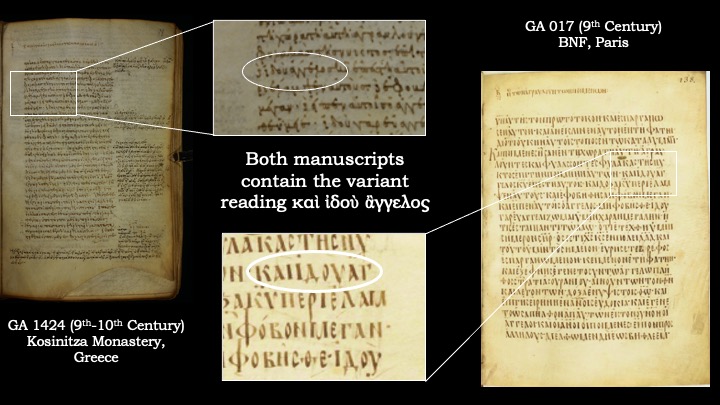

We find the nativity account continues in the different classifications of Greek manuscripts that follow papyrus: majuscule manuscripts, minuscule manuscripts, and lectionaries. Majuscule manuscripts witness the nativity account. Some notable examples are Codex Sinaiticus (GA 01) and Codex Vaticanus (GA 03) (see below), as well as Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (GA 04), Codex Bezae (GA 05), Codex Cyprius (GA 017) and Codex Washingtonianus (GA 032). Majuscule manuscripts containing the Christmas story range from the third century to the beginning of the first millennium.

The great pandects, GA 01 and GA 03, not only display the stunning effort of scribes to copy Old Testament, Apocryphal, and New Testament books, but also contain a text that scholars often refer to as witnesses of an older text. Unique to each of these manuscripts are the many columns that the scribes fit onto the large parchment pages.

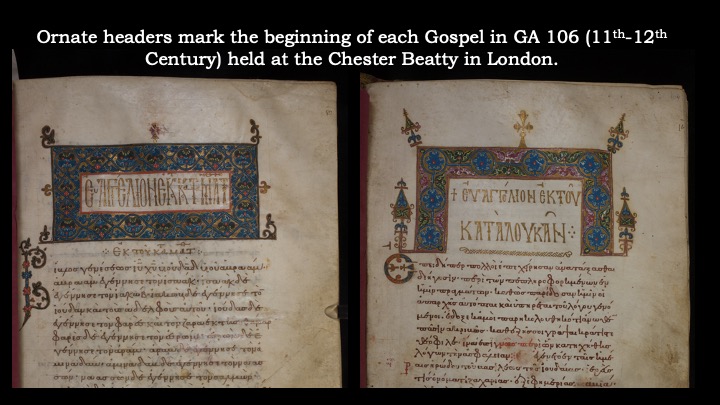

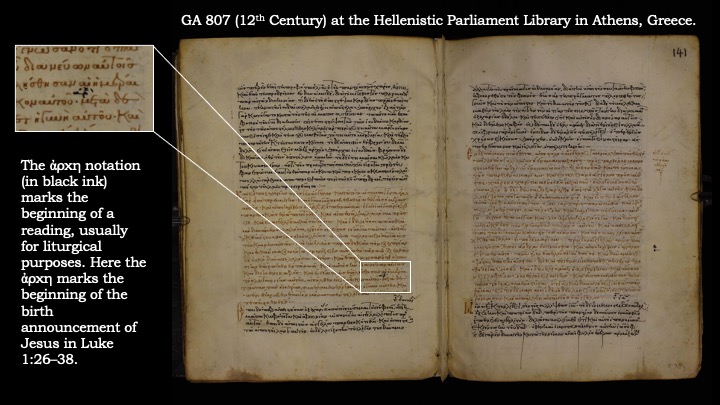

Finally, hundreds of minuscule manuscripts and lectionaries contain some or all of the beginnings of Matthew and Luke. Since minuscule print dominated a later time when greater manuscript production took place, we have many more copies of these kinds of manuscripts. The “clothing” that adorns these New Testament manuscripts—covers, decoration, readers aids, color, commentary, etc.—teach us about how the communities that read these copies valued and understood them. Minuscules take us through centuries of developing handwriting styles, manuscript ornamentation, and special markings for liturgical uses.

Textual critics utilize this large body of ancient literature—an “embarrassment of riches” as New Testament scholars are fond of saying—to determine the story that scribes so faithfully copied through centuries. To accomplish this, scholars study places where the copies differ from one another seeking to determine which reading best explains the rise of the others. This enables text critics to confidently determine the text that stood at the head of the long stream of the copies that followed.

Variants

One Christmas story variant occurs at Luke 2:9 where the oldest witnesses along with significant others (א B L W Ξ 565. 579. 700. 1241) read καὶ ἄγγελος (“and an angel”) while later (but some still early) sources (A D K Γ Δ Θ Ψ f1. f13. 33. 892. 1424. 2542. 𝔐) read καὶ ἰδοὺ ἄγγελος (“and behold, an angel”). The addition of ἰδοὺ appears in more manuscripts, most of the Byzantine text, yet due to its absence in more of the older copies that more strongly attest to an older text, the manuscript evidence indicates that the omission better reflects the original.

In Linus’ King James recitation we hear the familiar translation: “And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them.” Because the King James Version is based on a text that contains ἰδού, the verse is translated “Lo!” or “Behold!” The variant probably arose as a scribal accident or harmonization because Luke uses the word ἰδού ten times between chapters one and two of his Gospel. So it seems likely that somewhere along the line a scribe added an 11th ἰδού without noticing. Just as likely, a scribe could have added the word to bring the phrase into conformity with Luke’s pattern. In their work, text critics do find that longer texts usually involve scribal additions rather than attesting to the original. With almost the same weight, though, one might consider whether a scribe simply skipped over the small word. Bruce Metzger notes in his textual commentary on the passage, it is difficult to imagine why a scribe would have deleted this one ἰδού when it is among such a grouping. Internally, the scales slightly tip in favor of the omission.

At the end of the day, when weighing in the witnesses attesting to the different readings (or the external evidence), the omission appears to have been the initial wording with the inclusion of ἰδου added later. With thoughtful consideration, we can look at the evidence and confidently identify the reading that demonstrates the stronger case for originality. Most Bibles today prefer the shorter version and leave the ἰδού out of Luke 2:9. However, for those of us who grew up watching Linus ease Charlie Brown’s frustration, the variant ἰδού may remain in our memories of Christmas forever.

Conclusion

The above discussion of the variant found in Linus’s speech serves as an example. Matthew 1–2 and Luke 1–2 contain many other instances in which text critics wrestle with the evidence to determine which reading preserved the original text. Some variants even bear on the interpretation, the most prominent in the nativity account found in Luke 2:14 (for a discussion on this variant see note 44 of Luke 2 in the NET Bible). That does not mean, though, that we must throw our hands up as Charlie Brown in exasperation. Working through the abundance of evidence, we find a reliable text that passed through many hands over the centuries. Manuscripts preserved this story first read by candlelight, later amidst ceremony, and eventually by Linus to the Peanuts gang. Though copies contain differences, which sometimes become a familiar text to our ears, the ongoing work of text critics who study Greek New Testament manuscripts provides continual confidence about what the Christmas story says. Through the centuries the story has provided the response to the question, “Isn’t there anyone who knows what Christmas is all about?”

See the Christmas story in manuscripts through the centuries here

Resources about the Text of the New Testament and Manuscripts:

The Text of the New Testament, by Metzger and Ehrman

Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism, by Hixson and Gurry

Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament, ed. Wallace